Silver Tram - King Levon I (Leo, Leon or Lewan)

Mint - Sis

Born: AD 1150 (est)

Lord of Cilicia: AD 1187-1198

King of Armenian Cilicia: AD 1199-1219

Obverse: Seated Crowned Figure Holding Cross and Fluer-de-lis - Text: "Levon King of the Armenians"

Reverse: Cross Between Two Lions Rampant - Text: "By the Will of God"

|

This is a silver tram of Levon I, the tenth Roupenian (Rubinid) prince of Cilician Armenia and its first king. He is variously referred to as Leo II, Leon II, Lewan, Levon II as a prince, Levon I as King. He is also often referred to as "Lord of the Mountains" or "Levon the Magnificent".

Obverse: Depiction of King Levon I enthroned facing, crowned with mantle and sitting on a lion throne. He holds a cross in his right hand and a Fluer-de-lis in his left hand. The inscription in Armenian states "Levon King of the Armenians."

Reverse: Depiction of a long cross between two lions rampant looking back at the cross. There are dots in each quadrant of the cross and three dots above the heads of the lions, possibly denoting a crown. The inscription in Armenian states: "By the Will of God." Mesrop Mashtots: The Armenian Alphabet The inscriptions on these coins are in the distinctive characters of the Armenian alphabet that was invented and introduced by the Armenian linguist, statesman and theologian Mesrop Mashtots in AD 405. Mashtots was from an Azar family, or a family who was of the lower nobility, and whose education earned him an appointment as secretary to King Khosrov IV.While always at a cross roads between larger, more powerful kingdoms and empires, at this time Armenia had become a battle ground for the incessant wars between the Romans and Sassanid Persians who eventually divided the kingdom into Eastern and Western Armenia with the Peace of Acilisene around AD 387. The smaller Western half went to Arshak III (Arsaces II) who served as client monarch to the Roman Empire under Theodosius I while the East went to the Sassanids under Shapur III. Soon after Arshak died and western Armenia was made a province under the direct rule of the Roman Empire causing many Armenians, particularly those of high rank, to move to Eastern Armenia and petition the Persians for a new king. Shapur granted them a new king in the form of Khosrov IV who was probably a prince of the Arsacid dynasty, the successors of the Artaxiad Dynasty, who were themselves the successors to the founding Orontid dynasty. He was crowned as the King of Eastern Armenia by Shapur III at the request of the Armenian nobility. While the religion of the Persian Empire was Zoroastrianism and Armenia had been a Christian since it was made the official religion of the kingdom around AD 301-314, they continued as a Christian kingdom under Persian rule.

Shapur III died in AD 388 and was replaced by Bahram IV who was also Khosrov's nephew by his marriage to the Daughter of King Shapur III. Bahram IV was not pleased with Khosrov because of his tendency to act without consulting his Sassanid overlords and he soon removed him from power and imprisoned him. Khosrov was replaced by his brother Vramshapuh (AD 298) who retained Mashtots as his secretary. As he ruled a fragmented kingdom and wielding a much diminished authority, the mission of the Armenian King and Church during this time of upheaval, and as a part of a pagan empire, was to strengthen the Armenian Church and unity within the Armenian population. Although the people spoke the Armenian language, there was not a written form of this language so all religious and state documents were in Greek, Persian or Syriac. Mesrop Mashtots, with support of the Patriarch Isaac of Armenia and Vramshapuh, developed the Armenian alphabet with which they could bring the bible, Armenian history and literature to the people in their own language. For this contribution to the Armenian people Mashtots was made a saint and is a highly revered figure in Armenia where his alphabet is still in use today.

Armenia

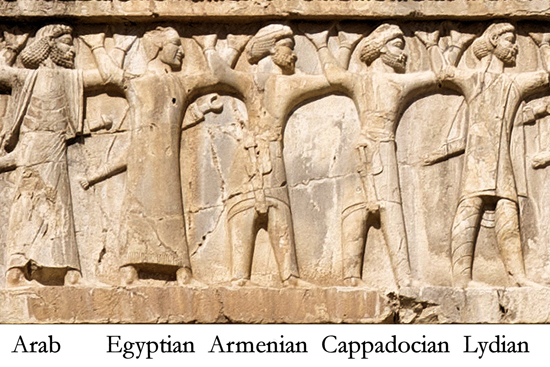

The first definitive mention of a polity and people that can be identified as Armenia, and Armenians, in the historical record is in the inscriptions that accompany the relief carvings on Mount Behistun in the Kermanshah province of western Iran. Commissioned by the Achaemenid King of Persia Darius the Great between 522 and 486 BC, the Behistun carvings serve as a resume of sorts for the Persian King of Kings and King of Nations. There he inscribed in three languages (Persian, Elamite and Babylonian) for posterity his illustrious lineage and the subject nations under his rule. There are twenty-three subject nations mentioned, number eleven being both 'Armena' or 'Urartu' depending on the language. This inscription shows that at this stage Armenia now existed but was still being viewed as interchangeable with Urartu, a name used for the region that was previously ruled by the Kingdom of Van, and the territory that Armenia occupied after the fall of that kingdom. How Urartu became Armenia is still a matter of debate. Urartu, or more correctly the Kingdom of Van situated in Urartu, was in decline after centuries of dominance, weakened by war with Assyria and repeated raids by Cimmerians and Scythians. The kingdom eventually made peace with the Assyrians which offered a measure of protection and stability, but with the subsequent decline of the Assyrians, the kingdom fell victim to what may have been a combined attack by Median and Scythian forces. Urartu ruins suggest destruction by fire that ended the rule of Rusa IV, the last King of Van in about 590 BC. Eventually Urartu disappears from the historical record in the early 6th century BC to be replaced by Armenia. The Assyrian King Shalmaneser I (1263-1234 BC) subdued and annexed Urartu into his growing empire and in his annals he describes the region at that time as the home to eight territories that were not unified. It is possible that the Armenians were one of these groups native to this territory. This group may have allied with the Median invaders and taken power after the defeat of the Kingdom of Van who had, since the rule of Shalmaneser, taken control of the region. It is possible that the Armenians were just a new dynasty that replaced the previous ruling dynasty of Van with the help of these invaders. It is also possible that the Armenians may have been of Persian origin as, from very early on after they take control of the region, they are closely allied with the Persians through familial ties to the Achaemenids. Urartu / Armenia may have been first under the rule of the Medes who conquered the territory, and its early monarchs possibly ruled as client kings starting with the semi-legendary first King Orontes I (circa 570 BC) who is considered the first King of Armenia and the founder of the Orontid Dynasty. He was followed by his son Tigranes who may have worked to end Median dominance in Armenia and ally with Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Tigranes was succeeded by Hydarnes who was a Persian nobleman of the Orontid Dynasty and closely aligned with the Achaemenids. He is mentioned in the Behistun inscriptions as one of six conspirators who supported Darius I (The Great) against the legitimate Achaemenid monarch Bardiya. Hydarnes and his successors are seen to be both Achaemenid and Orontid and Armenia both a Satrapy, or a state, of the Persian empire, and a kingdom. As a Satrapy of the Persian Empire under Artasyrus the Bactrian, Armenia comes into clearer focus, and even more so under his son Orontes I in 401 BC. Both are represented as being somehow a part of the Orontid Dynasty ruling Armenia for the Achaemenid. Orontes the Bactrian was succeeded as Satrap by the future King Darius III Codomanus, the last King of Kings of Persia. During his reign the Kingdom fell to the forces of Alexander the Great after Darius III repeatedly fled the battlefield, most notably at the Battle of Gaugamela after which he died at the hands of his own men in 330 BC.

After the fall of Urartu, a state of Armenia would exist in some form or another, and with varying levels of autonomy, for close to a thousand years under the rule of three dynasties: Orontid 6th Century BC - c.200 BC, Artaxiad 189 BC - AD 12, and Arsacid AD 12 - AD 428). In the Middle Ages Armenia would rise again under three final dynasties (Bagratid, Roupenid and Hethumid) who claimed connection to the Arsacid line. In its long history Armenia managed to walk a fine line with the great nations that surrounded it, often willing to concede rather than resist when facing powerful kingdoms and empires. In return for their concessions they often retained some level of autonomy and, in some cases, became close and valuable allies as in the case with the Persians with whom they were not only allied but shared familial ties. Armenia rarely ruled as an independent Kingdom. Armenia was a Satrapy of the Persian Empire, under Greek rule after the fall of the Persians then under Seleucid rule with the disintegration of Alexander's empire. For a brief time Armenia expanded to become an empire under King Tigranes II before becoming a Roman client kingdom, a buffer state and a theater of war for the interminable conflicts between the Parthian, and later Sassanid Persian Empire, and the Roman, and later Eastern (Byzantine) Roman Empire. Armenia was partitioned several times between the two empires with the Western part eventually becoming a province under direct Roman rule while the kingdom continued for a time as clients of the Persians. Perpetual war between these two empires left them both weakened making them ripe for conquest during the meteoric rise of Islam, and the rapid conquest of territory by forces under a succession of Islamic Caliphates. The rise of Islam meant the relatively rapid fall of the Persian empire, a loss of territory for the Eastern Roman Empire, a perpetual foe close by for the Christian Empire and it also meant the fall of Armenia. Roman Armenia fell to the Rashidun Caliphate in AD 639 and Eastern Armenia fell soon after in AD 645. Armenia would still exist but as a territory of the Rashidun, and the successor Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, as well as the various local emirs who exercised power in the territory. The fall of the Persian Empire did not put an end to the perpetual war between Eastern and Western powers who had made the near and middle east their battlefield for many centuries. This conflict between east and west would not only continue but, in many ways, it would become considerably worse. With the rise of these religions that now dominated their respective spheres, both sides now embraced monotheistic religions that shunned all other faiths, and variations of their own faiths, as enemies of God. Although these wars remained conflicts primarily revolving around land and resources, what all wars are fought over, these religions injected an added element, the domination of one religion over the other, one doctrine over the other and one God over the other. Religious intolerance as a justification for wars of conquest. In the middle were the Armenians who submitted to Islamic rule but largely remained Christian. At times they were granted religious freedom as a minority, at other times they were aggressively targeted for conversion. Through the subsequent years many Armenians relocated into Byzantine territory where they often joined the military and built Armenian communities. While they often enjoyed a measure of acceptance for their religious beliefs, they had largely lost the autonomy, or semi-autonomous status, they had so often enjoyed in the past. Armenians lived under more direct Eastern Roman or Caliphate rule, often in communities formed in border regions, until the rise of the Bagratid Dynasty. The Armenian Kingdom was reestablished under King Ashot I as an official buffer state, with approval from both the Islamic and Christian powers. Ashot I was sent a crown from both Basil I of the Eastern Roman Empire and the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mu-Tamid, and he was crowned as King of the Armenians around AD 884-885. This new Kingdom would walk a fine line attempting to placate both Byzantine and Caliphate while keeping them at arm's length. This kingdom too would fall, partly due to internal conflicts, but more significantly by external threats in the form of steady and increasingly more aggressive encroachment by both Byzantine and Seljuk forces resulting in the collapse of Bagratid rule and the exile of its last King Gagik II in AD 1045.

Armenians in Cilicia and the Rise of the Roupenids There was already an Armenia presence in Cilicia at least as far back as its conquest by Tigranes the Great around AD 83. Islamic forces under the Abbasid Caliphate took Cilicia in the 8th century, at that time a part of the Eastern Roman Empire, making it a buffer state. It was retaken by the Emperor Nicephorus II in AD 965 after which it was increasingly settled by Armenians, many of whom had entered into the service of the empire as soldiers or government officials. The conquest of Armenia by the Rashidun Caliphate, then the reconquest of the area by the Byzantine Empire, only for it to be taken again by the Seljuk Turks, caused further migrations of Armenians into Byzantine territory with many settling in Cilicia. After the fall of the Bagratid dynasty and the occupation of their homeland, Armenians were in a state of flux and further upheaval was caused by the defeat of the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV by the Seljuk Turks under Alp Arslan at the Battle of Manzikert close to Lake Van in the Armenian Highlands. Many of these migrants into Cilicia, like the Armenian General Philaretos Brachamios, who served the Emperor at Manzikert, settled in Cilicia and established fiefdoms there, compelling other Armenian nobility to do the same, ostensibly as vassals to the Emperor at Constantinople. Roupen, an Armenian nobleman and general who claimed kinship with the Bagratid King Gagik II, came to Cilicia in c. 1080 and settled in the Taurus Mountains north of Sis, based in the Fortress of Kopitar. This area was ideal in that it was difficult to access and easier to defend. Here he broke with the Byzantine Empire and launched successive military campaigns to capture Byzantine territory and enlarge his own domains. Roupen was not the only Armenian lord in Cilicia, nor was he the most powerful but by the time of his death he had captured several strongholds including the Fortress of Pardzerpert which became his base of operations. He was the vassal of the more powerful Philaretos Brachamios who was seen as a usurper by the Byzantines and was eventually defeated by the Seljuk Turk Alp Arslan. After his death, the remains of his diminished territory was relinquished to Baldwin II by his sons during the first Crusades and incorporated into the County of Edessa and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Roupen was the first Armenian "Lord of the Mountains". He and his son and successor Constantine worked to expand and solidify their hold on Cilicia and further fortify their territory against attacks from both Byzantine and Seljuk forces, both of whom launched repeated attacks seeking to dislodge them from their mountain refuge. Constantine is considered the first to lay a lasting foundation for Roupenid rule in Cilicia. He chose to offer material support to the Crusaders, assisting them in taking Antioch in 1097. For his help, which was crucial to their success, Godfrey de Bouillon and other leaders of the First Crusade rewarded Constantine with the royal titles of Baron and Count. Joscelin, the Count of Edessa, married his daughter and Godfrey's brother Baldwin would marry his niece. In this way the Armenian lords of Cilicia created familial ties to Crusader states gaining powerful allies in the 'Franks'. Thoros I, the successor and son of Constantine who died in c. AD 1100/1103, continued good relations with the Crusaders and further expanded Armenian held lands making the city of Sis his capital. Thoros died around AD 1130 and his son and heir Constantine II died soon after him, possibly by poison, and was succeeded by Levon I (Leo I or Leon I), brother of Thoros and the youngest son of Constantine I. The reign of Leo I saw renewed attempts by the Byzantine Emperor to retake Cilicia which ended in the loss of Armenian held territory and Leo's capture in AD 1137. The Emperor John II invited Leo to meet and negotiate terms but instead captured both Leo and his sons Roupen and Thoros. Leo and Roupen died in captivity while Thoros escaped, possibly in AD 1145 and succeeded his father as Thoros II. Upon his return he wasted little time rapidly retaking much of what was lost to the Byzantines and more by AD 1148. He successfully resisted numerous Byzantine offensives as well as offensives by the Turks and reestablished Armenian control over Cilicia. Thoros abdicated the throne in AD 1169 in favor of his young son Roupen which caused conflict with his brother Mleh who was either expelled or fled to Aleppo, at that time under the rule of the Emir Nur-ed Din and, at some point, converted to Islam. He then invaded Cilicia with the aid of the Emir, killing his nephew Roupen in AD 1170. Once in power Mleh was in turn murdered by the son of his brother Stephen, also called Roupen, in AD 1175 who then ruled as Roupen III. Although generally characterized as a good ruler who continued good relations with the Crusaders, he came into conflict with Antioch which was at that time under the rule of Bohemond III. Bohemond allied with rival of the Roupenids, Hethum III of Lampron, of the Hethumid Family, a powerful Armenian family that maintained a close alliance with the Emperors in Constantinople. The two invited Roupen to Antioch to settle their disputes in AD 1183 only to capture and imprison him upon his arrival.

The Rise of Levon I and the Resurrection of the Kingdom of Armenia Levon (or Leo / Leon) was the second son of Stephen and grandson of Leo I. Stephen was the third son of Leo I who was appointed as a Marshall by his father to assist in defeating the forces of the Emperor John II Komnenos who had renewed attempt to retake Cilicia. Levon's father is depicted by the contemporary diplomat, military leader and historian Smbat Sparapet as having a "Wicked Nature." According to Sparapet, he conducted raids and took territories from the Sultan Kilij Arslan II of Rum, threatening a peace brokered between his brother Thoros and the Sultan. He later repeated his unilateral attacks, this time taking Byzantine territories in answer to their aggressive actions and repeated incursions into Cilician territory, again threatening the recent reconciliation his brother had brokered with the emperor Manuel I. Stephen was invited to a banquet by Andronicus Euphorbenus, the Byzantine governor of Tarsus, on the pretense of making peace and was instead murdered there for his actions. Whether Thoros disapproved of Stephen's actions is not known for certain but the death of his brother brought reprisals. Upon his brother's death, Thoros attacked Manistra, Anazarbus and Vahka, killing the Greek soldiers Garrisoned there, and soon after again made an uneasy peace with the Emperor who recalled Euphorbenus for the killing of Stephen. After another war against Cilicia with little real success, The Emperor Manuel finally gave up his claim to Cilicia and recognized Thoros as the lord of that territory on the condition that Byzantine merchants would retain access to the ports and that Thoros accept the Emperor as his liege.

Upon the death of his father, Levon lived with his uncle Pagouran of Barbaron where he helped to guard the Cilician Gates. With the death of his uncle, his brother was raised to power as Roupen III and, without an heir, Levon became the heir apparent. When Roupen was captured by Bohemond III and Hethum III of Lampron, Levon was elevated as the caretaker for his absent brother and was expected to resolve the dire situation. Levon first went to war with Hethum III as the forces of Bohemond marched on Cilicia but failed to make significant progress. In the end Levon promised to pay a ransom and handed over territory and hostages for the release of his brother. Once the ransom was paid, the hostages were released and Levon wasted no time taking back the territory he had ceded. Upon his return, Roupen III handed over power to his brother in AD 1187 and retired to a monastery. Levon II, the 10th Lord of the Mountains, immediately took to the field and routed Turkish forces who had invaded and were looting in the northern part of Cilicia. He then attacked the Seljuks in AD 1188 taking the Fortress of Bragana and Seleucia before taking Heraclea, which he ransomed for a tidy sum, and then on to Caesarea. Hethum of Lampron, who had come to terms with Levon and was now in his service, took the important fortress of Loulon. It was clear that the Armenians of Cilicia were now more unified than ever, and in firm control of their territory under the leadership of Levon.

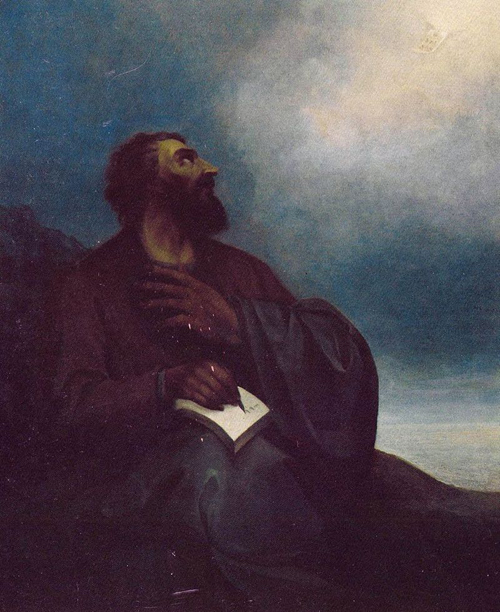

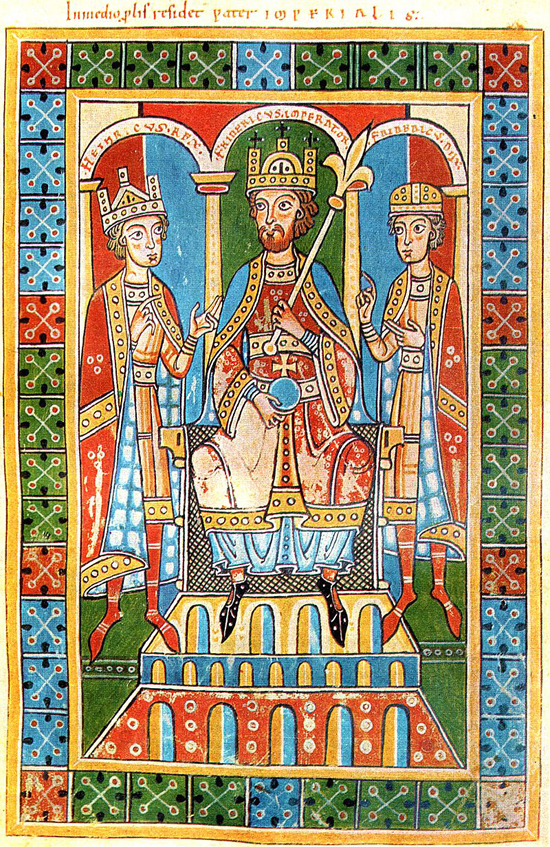

When the Emperor Friedrich Barbarossa reached Cilicia in AD 1190, he was met by an Armenian embassy sent by Levon II which brought badly needed supplies. Shortly after his arrival the old emperor passed away. This was a terrible blow to Levon as he had been promised a crown by the Emperor, to be made King, and the emperor's son Friedrich VI, Duke of Swabia, and the other nobility in the ranks of the crusaders, did not commit to fulfill the former emperor's promise. Still he aided the soldiers of the Third Crusade and joined them during the siege of Acre and the conquest of Cyprus.

Again animosity arose between the Armenians of Cilicia and Antioch when Levon took the Fortress of Baghras in AD 1191, a former possession of the Knights Templar, which had been taken by Saladin. Levon drew the animosity of the Templars, who believed they were the rightful owners of the fortress, when he refused to return it to them. He then took Bohemond III captive, ostensibly over debts not paid but more likely because he coveted the Principality of Antioch. Indeed he sought to annex the principality of Antioch but this planned failed as he was, in the end, rejected by to people there. He did, however, force Bohemond to relinquish his suzerainty over the Armenian lards of Cilicia before releasing him in AD 1194. He also gave his niece Alice, daughter of Roupen III, to Bohemond's son and heir Raymond in marriage. He now had a family connection to the Principality in the form of his niece and any possible child she may have with Raymond. In AD 1197 his requests were finally heard by Pope Celestine III and the Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich VI. An embassy was sent east that carried two crowns, one for Aimery of Cyprus and the other for Levon. However there were concerns regarding differences in the rites and doctrine of the Armenian Church and the Latin Church and these concerns were voiced on both sides. There was an expectation that the Armenian Church would conform to the Latin rites to the objection of the Armenian clergy. Levon would not be denied his crown and made it clear to the Armenian clergy that they would promise what needed to be promised to assure them that they would comply even if they had no intention of doing so. With these assurances Levon was crowned King of Armenia as Levon I (Leon I or Leo I) at the Cathedral at Tarsus on January 6, 1198. To the Armenians this signified the end of their diaspora and the restoration of the Armenian Kingdom. He reportedly also received a crown from the Emperor in Constantinople Alexius III at around the same time.

Bohemond III died in AD 1201, and with his death began the war of succession for the Principality of Antioch. His son Raymond passed away in AD 1197 and Bohemond supported his younger son Bohemond of Tripoli as his successor, seeking to bypass Raymond's son with Alice Raymond-Roupen. After Levon's coronation, the new king made Raymond-Roupen his successor to the Armenian throne and his junior partner. Levon championed the elevation of Raymond-Roupen seeking to take control of the Principality of Antioch through his young nephew. Although there was some support for Raymond-Roupen in Antioch, and with help from Levon he was installed as Prince of Antioch in 1216, his support dwindled and he was overthrown in AD 1219 by Bohemond of Tripoli who ruled as Bohemond IV. As a consequence of the war of Antiochene succession, Levon was faced with renewed attacks by the Seljuk Turks allied with Bohemond of Tripoli. Although he faced losses because of his obsessive quest to make the Principality of Antioch a part of his domains, he ultimately preserved his kingdom. Levon I died in 1219 and was succeeded by his young daughter Isabel, with Constantine of Lampron as Regent, passing over Raymond-Roupen who pushed his claim, with some support, to the throne. When he attempted to take the throne by force he and his supporters were defeated and he was imprisoned where he died soon after. Constantine then sought to marry Isabel to a prince choosing Philip, the son of Bohemond IV of Antioch, but Philip had a disdain for the Armenians that he could not hide and they soured on him. He was also imprisoned where he died soon after, possibly of poisoning. Finally Constantine married Isabel to his own son, joining the Roupenids to thier former rivals the Hethumid of Lampron, who reigned as Hethum I and ushered in the Hethumid Dynasty as the new rulers of Armenia. Under the rule of Levon I, Armenian Cilicia was at its height. Levon made many strong alliances and was able to navigate the rocky waters of Crusader politics quite well. While there were plenty of bumps in the road he generally maintained good relations with the crusader states as well as the Holy Roman Empire and the so called 'Frankish Kingdoms'. He also had generally good relations with the Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller, and Teutonic Knights and joined his family in marraige (as some of his predecessors did) into powerful crusader families further strengthening alliances. He was even able to keep mostly cordial relations with the Emperor in Constantinople while keeping the various Islamic Emirs and Sultans at arm's length. Levon improved the infrastructure of Cilicia building fortifications and improving his ports which in turn improved commerce and trade through alliances with the Venetians and Genoese whom he granted special privileges. Both land and sea trade, both domestic goods and foreign goods heading to the east or the west, greatly expanded as merchants found safe routes through his lands, off his shore and safety at his ports. All of this contributed to enlarging the coffers of the monarch and his court that often spent liberally on building projects like new churches. Through his close association with the Latin Kingdoms of the west his court and governance adopted a more western manner in structure, protocol and laws.

The Kingdom of Armenia in Cilicia, slowly becoming surrounded by ever more hostile neighbors, lasted until King Levon V (born Guy de Lusignan) who finally surrendered to Mamluk forces in AD 1375. Thus began again a long period of Diaspora, often living in close knit communities, mostly rural, as a minority Christian population in majority Islamic states.

At times Armenian communities and the Armenian Church enjoyed a measure of freedom under the multicultural Ottoman Empire, however the multicultural nature of the empire also bred various nationalist and independence movements. To deal with such systemic problems the empire sought to 'Ottomanize' the disparate people and cultures within its borders to promote Turkish Nationalism as well as Pan-Islamism. By 1915 many factors such as internal political upheaval, unfavorable land reforms, civil unrest, ethnic and cultural clashes, war and nationalist movements like the socialist Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun) lead to accusations of Armenian revolutionaries conspiring with the Russians and desertions from the military by Armenians. This in turn led accusation that Armenians were the cause of the Ottoman defeat against Russian forces at the Battle of Sarikamish. These accusations were accompanied by ever harsher reactions from both local authorities as well as the Ottoman state driving Ottoman leadership to dismiss Armenians from state and military service, executions of those who were seen as conspirators and agitators, and eventually the systematic forced resettlement of Armenians in order to keep them from settling together in large numbers. These resettlements became forced marches into the desert with little to no water or food resulting in starvation, brutal treatment, forced conversion, enslavement and mass killings with a death toll estimated to be more than a million Armenian lives lost. These massacres were recognized and condemned very early on by the Allies and even the Grand Vizier Damat Ferid Pasha publicly admitted that about 800,000 Armenian Ottoman citizens had lost their lives due state policy. Trials were held and perpetrators were found guilty however few if any were held accountable. The treaty of Sevres of 1920 awarded land in Asia Minor to the Armenians but it was never ratified, however Armenians had already staked their claim on territory leading to the establishment of the short lived Democratic Republic of Armenia in 1918, the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1920 and finally the Republic of Armenia in 1992, the current nation of Armenia, again located in the Armenian Highlands in Western Asia. |